Elvira van Groningen - April 2024

Introduction - Performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians

Playing a musical instrument is one of the most challenging tasks that the human brain and body can perform (Steinmetz et al., 2010). Musicians work under extensive internal and external pressure to reach ultimate perfection (Steinmetz et al., 2014). The unique psychological and physical demands facing the professional musician are well recognised and put them at high risk for developing playing-related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMDs) (Ackermann et al., 2022), frequently defined as ‘pain, weakness, lack of control, numbness, tingling, or other symptoms that interfere with your ability to play your instrument at the level you are accustomed to’ (Zaza et al., 1998, p. 2016). PRMDs present themselves in many forms and can range from back, shoulder and neck injuries to hand and embouchure problems (Kok et al., 2016). Reported lifetime prevalence rates in musicians vary from 62-93% (Kok et al., 2016) with higher rates seen among string instrumentalists compared to wind players (Steinmetz et al., 2010).

PRMDs are considered multifactorial health issues (Rousseau et al., 2023), i.e., several factors are said to play a role in their manifestation. Sex, age and numbers of years played, BMI, nutrition and hydration have all been cited as associated factors, as well as practice habits, playing hours, the sudden increase of those playing hours and insufficient rest (Ackermann et al., 2012, 2022; Kochem & Silva, 2018; Kok et al., 2016; Zaza & Farewell,1997). Additionally, the repertoire and instrument played, as well as performance anxiety, emerged as important risk factors (Baadjou et al., 2016; Brandfonbrener, 2000). Several physical variables have been considered to have a significant influence on PRMDs, including instrumental technique, posture and positions associated with playing the instrument, and repetitive movements (Ackermann & Adams, 2003; Steinmetz et al., 2008). Lastly, deficits of the body’s deep stabilising systems (Steinmetz et al., 2010) and insufficient guidance from physicians and teachers (Zinn-Kirchner et al., 2023) also deserve to be highlighted as risk factors.

Understanding the mechanisms that influence the development of PRMDs is important so that more can be done to prevent and treat these oftentimes debilitating problems. Despite increasing efforts to prevent PRMDs, they were as frequently reported in a systematic review from 2016 (Kok et al.) as from 1998 (Zaza). They can affect musicians’ ability to play their instrument, with some musicians forced to temporarily stop playing or even terminate their career prematurely (Ackermann et al., 2012). This can lead to financial concerns for the musicians, and in some cases their employers, and has a considerable psychological and social impact on those affected (Kok et al., 2016; Zaza et al., 1998).

Violinists’ neck and shoulders

Studies show that violinists are particularly susceptible to developing PRMDs (Baadjou et al., 2016) and that they experience high rates of injury in the neck and shoulders specifically (Dos Santos et al., 2024). For these reasons, this essay will discuss risk factors associated with shoulder and neck disorders in violinists, as well as the prevention and treatment thereof.

2.1. Playing the violin To understand the specific needs and challenges of violinists, some knowledge of the violin itself is necessary. The violin is a wooden, hollow instrument with four strings. The neck of the instrument is held by the left hand, while its body rests on the left shoulder. The chin can be placed on a chin rest to stabilise the violin. The bow is held with the right hand and creates vibrations by pulling the strings horizontally. The vibrations resonate within the body of the instrument, amplifying the sound. The left hand's fingers change the sound's pitch by pressing the string onto the fingerboard.

Figure A: A violin and bow: 1, body of the violin; 2, fingerboard; 3, tuning pegs; 4, fine tuners and tailpiece; 5, bridge and strings; 6, chin rest; 7, bow; 8, tip of the bow; 9, frog of the bow

Due to the separate tasks, different demands are placed on the left and right arm. The left arm needs to hold up the violin in a static position, outwardly rotated in the shoulder joint with the left forearm constantly supinated, permitting the fingers to reach the strings. The right arm performs more dynamic movements, continually flexing and extending at the elbow and wrist joints to control the movements of the bow. Moreover, the right arm needs to be abducted (i.e., lifted) significantly, especially to play on the lowest string. It also needs to be internally rotated at the shoulder joint with the forearm in a pronated position.

2.2. Playing-related shoulder and neck anatomy The main muscular support for the arms and the instrument can be found in the shoulders (Dos Santos et al., 2024). One important factor is the position of the shoulder blade, ideally providing stability during the activity of the hands whilst offering mobility of the arm (Voight & Thomson, 2000). The glenohumeral joint (where the arm bone articulates with the shoulder blade) is in fact one of the most movable joints in our bodies, allowing the arms an almost unrestricted range of movement. At the same time, this makes for a very vulnerable shoulder structure (Prescher, 2000).

Figure B: The shoulder (or pectoral) girdle, consisting of the scapula (shoulder blade) and clavicle. See also the glenohumeral joint and the sternoclavicular joint.

Furthermore, the shoulder girdle, consisting of the scapula and the clavicula (see figure B) only has one bony connection to the trunk, between the clavicle and the sternum (sternoclavicular joint). All in all, the shoulder muscles need to work optimally to provide dynamic stability to the shoulder girdle, and consequently to the arm and hand connected to it. The position of the scapula depends on the tension, length and recruitment of the shoulders’ stabilising muscles (Briel et al., 2020). For example, the lower part of the trapezius muscle is optimally used for stabilising the scapula (Lindman et al., 1990), and so is the serratus anterior, which helps to stabilise the shoulder girdle during arm movement (Ledermann, 1996) (see figure C). Finally, in order to stabilise the instrument itself, rotation and/or lateral flexion of the neck is necessary to allow the chin to reach the chin rest (Park et al., 2012)

Even though playing the violin should not be painful in physiological circumstances, (Zinn-Kirchner et al., 2023), several risk factors play a role in the high incidence of injury in violinists.

Figure C: The serratus anterior and trapezius muscles

Risk factors

Holding the violin, and playing it, can lead to discomfort in the neck and shoulders (Dawson, 2002). Specific risk factors can be found for developing PRMDs in this part of the body.

3.1. Increased risk for violinists

Musicians who work with both their arms elevated, as violinists do, are shown to be more susceptible to shoulder and neck problems than other instrumentalists who perform in a more neutral position (Nyman, 2007). The constant load of having to support the weight of the violin and hold up the bow arm, as well as the repetitive movements needed for playing, can stress the shoulder structure and may explain the high rates of shoulder injury (Ackermann et al., 2012; Dos Santos et al., 2024).

Painful symptoms in the neck and shoulders can also be attributed to the many hours of playing in these static positions (Wilke et al., 2011). String players tend to accumulate more hours of playing than other instrumentalists, as they often start learning their instrument at a younger age and tend to practise more (Jorgensen, 1997, 2001). The nature of the repertoire may also play a role; one study found that orchestral violinists play the highest number of bars out of all instrumentalists in the orchestra (Nyman et al., 2007).

3.2. Body mechanics of the shoulder and neck On a more biomechanical level, shoulder pain in instrumental musicians can be caused by impaired motion and instability of the shoulder blades, both associated with a weak serratus anterior muscle (Lederman, 1996). Lack of normal function of this (and other) stabilising muscle(s) can add extra load onto other shoulder muscles, triggering compensatory movement (Steinmetz et al., 2010; Lederman, 1996). For example, studies have found higher levels of upper trapezius activation and weakness of the lower, more stabilising part of the muscle in violinists experiencing neck pain (Kim et al., 2014; Park et al., 2012). The upper part of the trapezius muscle is more optimally used for movement, as opposed to stabilisation (Lindman et al., 1990). Crucially, a study by Steinmetz et al. (2010) found that 85% of musicians with PRMDs had impaired function of the scapular stabilisers. The inappropriate functioning of joints and muscles can eventually lead to changes in posture (Alinia et al., 2019).

3.3. Posture

Asymmetry of the shoulders can be found in violinists and among them, those who practise more seem to have greater abduction of the shoulder blades (i.e., moving outward from the midline) (Dos Santos et al., 2024; Savino et al., 2013). Other postural changes seen in many musicians are spinal deviations, such as thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis (Blanco-Piniero et al., 2015; Dos Santos et al., 2024). In fact, most musicians have been found to adopt incorrect postures, and are more likely to do so when performing than when posing without the instrument (Blanco-Piniero et al., 2015). Critically, a study by Araújo et al. (2009) found that all violinists in their study exhibited postural flaws, putting them at higher risk of developing PRMDs.

3.4. Postural stabilising systems

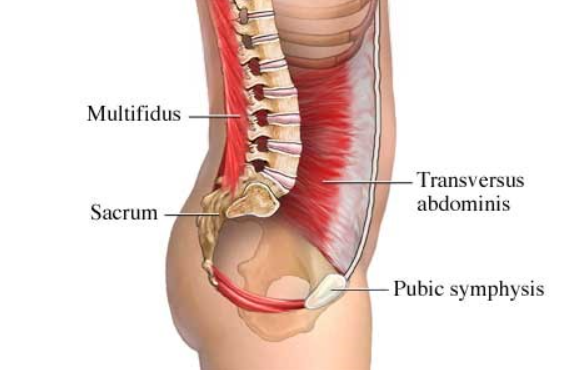

A possible explanation for this comes from a study by Steinmetz et al. (2010), which found impaired function of the deep stabilising muscles in musicians with PRMDs, especially among string players. Engaging the lumbopelvic stabilising system (the transverse abdominis and deep multifidus muscles, see figure D) can increase intraabdominal pressure and create more tension in the thoracolumbar fascia, thereby enhancing spinal stability (Cresswell et al., 1992; Hodges et al., 2001). Moreover, contraction of these muscles assists in maintaining equilibrium whilst limb movements add postural load. Ideally, this postural challenge is managed by the feedforward activation of the transverse abdominis, contracting milliseconds before the limbs move (Hodges et al., 1997). In turn, the spine and pelvic region can help to stabilise arm and shoulder function through the fascial system and the latissimus dorsi muscles, linking the lumbopelvic area all the way to the shoulder girdle. Failing to recruit the deep stabilising muscles of the trunk can lead to inappropriate, compensatory activation of more superficial muscles and result in pain and dysfunction in other areas, not only the lower back. The shoulder girdle, being inherently dependent on muscular stability, is particularly susceptible to dysfunction when superficial muscles (e.g., upper trapezius, levator scapula or pectoral muscles) become overactive, leading to altered movement patterns of the neck and shoulders.

Figure D: the transverse abdominis and multifidus muscles

3.5. Instrument fixation and position

Regarding stabilisation of the violin, repetitive lateral flexion of the cervical spine (i.e., bending the neck sideways), rather than rotating around its vertical axis, might contribute to neck pain in violinists (Park et al., 2012). Lateral flexion creates an asymmetrical posture and puts more mechanical stress on one side of the spine and neck (Wilke et al., 2011). The position of the instrument might also be associated with the occurrence of compensatory movements in the left arm and shoulder (Margulies et al., 2023), as well as with objective muscle tension and perceived muscular effort (Hildebrandt et al., 2021). Violinists with shorter arms may be at higher risk of pain, further emphasising the importance of optimal, individualised instrument positioning (Ackermann & Adams, 2003).

3.6. Teaching

Teaching traditions put forward a broad and frequently contradictory array of recommendations for an appropriate violin position, which in itself could be considered a contributor to the high rates of PRMDs (Margulies et al., 2023). Teachers often do not possess the necessary anatomical knowledge to adequately guide their students towards optimal biomechanics in playing (Détári, 2022), basing their tuition on their own education and teaching tradition, rather than evidence-based principles (Clark et al., 2016). Their oftentimes limited knowledge of how to instill healthy posture and sustainable playing habits (Farruque & Watson, 2016; Norton, 2016) is a risk factor that needs to be addressed.

Prevention

4.1. The violin teacher

As students develop their playing habits and attitudes towards health in the educational setting (Norton, 2016), teachers play a vital role in injury prevention. They can and should encourage postures, instrumental technique and practice habits that benefit the students and help them sustain a lifetime of playing (Guptill & Zaza, 2010). One of many responsibilities of the teacher is to help the student with the positioning of their instrument (Margulies et al., 2023). Appropriately fitting the instrument’s position and instrumental technique to the physical characteristics of the individual student may be one way to help prevent injury (Ackermann & Adams, 2003). The physical setup, for example, could be partly adjusted by use of accessories like chin and shoulder rests to reduce the need for lateral flexion of the neck (Savino et al., 2013).

4.2. Postural education

Given that improper posture was mainly seen to be adopted when playing, rather than posing, one might assume a direct link to playing technique. Therefore, more attention should be paid to teaching strategies (Blanco-Piniero et al., 2015). Postural training and prevention education for music teachers is needed, providing them with an appreciation and understanding of the physical aspect of playing their instrument, and thus the ability to give vital guidance (Farruque & Watson, 2014). Apart from protecting against pain and injury, optimal posture can allow musicians to expend a minimal amount of energy, while gaining maximal biomechanical efficiency during instrumental playing (Blanco-Piniero et al., 2015). This can lead to superior musical performance and shorter training times (Chan & Ackermann, 2014; Polnauer, 1952). 4.3. Health practitioners

Teachers do not need to become health specialists, but the increased awareness could at the very least enable them to identify potential risk factors and, where necessary, refer their students to qualified health practitioners (Waters, 2020). These practitioners would ideally offer an analysis of the individual’s movement patterns while playing (Kok et al., 2016; Steinmetz et al., 2008), and, if needed, help to adjust the physical setup and change any habitual automations that could lead to dysfunction over time.

4.4. The Timani method

One method that provides such analysis deserves to be highlighted. Timani, a recently developed somatic method for musicians, offers an analytical tool to identify compensatory movement patterns related to playing. It employs targeted exercises to change the less effective patterns into more functional ones. In addition, it includes the teaching of relevant anatomy and the direct integration of the newly learnt techniques into instrumental playing. The practical exercises can be used, for example, to become more aware of and strengthen certain muscles that are important for playing. An exploratory study found that Timani sessions can benefit playing posture, instrumental technique and performance-related body mechanics (Détári & Nilssen, 2022), and could consequently reduce the risk of developing PRMDs.

4.5. Strength training

A recent systematic review looked at multiple popular injury prevention programs for musicians, such as Alexander Technique, yoga and educational sessions, and found that strength training is most likely to reduce musculoskeletal complaints (Laseur et al., 2023). More specifically, strength training should target muscles that are fundamental for playing (Wilke et al., 2011) including, for example, the stabilising muscles discussed in the previous section on risk factors.

Interestingly, some risk factors are deemed ‘not modifiable’ by researchers (Chan & Ackermann, 2014; Guptill & Zaza, 2010), one example being gender (presumably referring to sex rather than gender). As females are consistently highlighted as more susceptible to PRMDs (Kok et al., 2016), this is a critical issue. The reason for females being more at risk than men is said to be due to the difference in muscle mass and strength (Steinmetz et al., 2010). Even though gender is understandably assumed to be unmodifiable, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the underlying cause of this gender imbalance (i.e., strength), is indeed modifiable through training.

4.6. Warm up routine

Although warming up before playing is frequently recommended as an important part of injury prevention, there is not much evidence for its effectiveness (McCrary et al., 2015; Zaza, 1994). For optimal performance, however, a recommendation from the world of sports could be relevant: an upper body warm up, defined as “an intervention that targets the upper extremity and/or core musculature and is designed to prepare the body for subsequent physical activity” McCrary et al., 2015, p. 1), should ideally closely mimic the required mechanics and movements of the activity. With this in mind, preparing and strengthening the relevant muscles and their coordination for playing could be an effective warm up routine and would likely enhance playing posture and instrumental technique, in turn reducing the risk of PRMDs.

4.7. Further prevention

Other prevention strategies, whose further discussion lies outside the scope of this essay, include music institutions’ dissemination of health education (Matei & Ginsborg, 2022) and provision of modifiable chairs with flat seats (Guptill & Zaza, 2010) to encourage the maintenance of a neutral spine. Even simple strategies, such as taking more frequent breaks, using relaxation techniques and the inclusion of mental practice can be helpful for musicians, especially if emphasised by music teachers and the musicians’ community (Zinn-Kirchner et al., 2023).

Treatment

Many musicians in need of support are wary of health professionals, often rightly concerned that they do not fully understand the complex challenges of their art (Ackermann et al., 2022). This highlights the importance of adequate prevention strategies in the first place (Wilke et al., 2011), and secondly, the necessity for enhanced care for performing artists (Ackermann et al., 2022).

5.1. Instrument specific intervention

As physiotherapy and manual therapy do not always prove successful in alleviating symptoms, more specific support is needed for those suffering from PRMDs (Steinmetz et al., 2008). Tailoring interventions to the specific needs of musicians, including the particular physiological and technical demands of playing their instrument, is vital (Steinmetz et al., 2010). One of the characteristics of the aforementioned Timani method is that it is developed specifically for and offered by musicians who have gone through training, bridging the gap between health professional and performer. Although it does not offer medical treatment, Timani has been shown to improve existing performance-related pain (Détári & Nilssen, 2022) by recognising and working on the underlying causes.

5.2. Physical therapy and exercise

In the context of physical therapy, a short continuing education course has been found to enhance health practitioners’ understanding of the unique demands placed on performing artists (Ackermann et al., 2022). According to Chan & Ackermann (2014), evidence-informed physical therapy must consist of physical examination that includes the observation and analysis of playing posture and the testing of strength and control of the muscles relevant to instrumental playing. Music performance biomechanical feedback should further inform treatment, which ideally comprises an exercise program to target any postural impairments and strengthen supportive musculature. One study by Chan et al. (2014) found a reduction of frequency and severity of PRMDs after an exercise program for musicians, and positive effects on their performance through enhancing posture and through the strengthening of muscles needed to support their playing. Furthermore, strengthening exercises for the neck and shoulders have been shown to help ease pain in the area, and increase endurance, in violinists (Alinia et al., 2019)

Similar to the strategies discussed in the prevention section of this essay, teaching new movement patterns can help alleviate existing symptoms (Détári & Nilssen, 2022), as well as preventing them from recurring (Steinmetz et al., 2008). Effective training should target the health of the musician and the quality of their playing, motivating them by improving both symptoms and performance (Blanco-Piniero et al., 2015; Wilke et al., 2011). Once again, this emphasises the importance of treating musicians in the context of playing their instrument.

Conclusion

In conclusion, given the high incidence and consequences of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians, finding effective prevention and treatment is imperative. Violinists seem to be particularly affected, with high rates of shoulder and neck disorders found in this population. The shoulder and neck are vulnerable areas that experience high demands during violin playing, requiring the surrounding muscles to provide optimal support. Among others, deficits of the deep stabilising muscles have been identified as a risk factor, leading to compensation in superficial muscles, altered posture, compensatory movement patterns and, ultimately, pain and dysfunction in the shoulder and neck area. Prevention should therefore be targeted at strengthening relevant muscles, analysing movement patterns and recognising and adjusting compensations, all in all enhancing posture and playing technique. The role of the instrumental teacher in instilling healthy playing habits cannot be understated. More education is required for teachers to gain a better appreciation of the biomechanical requirements of playing the violin. Similarly, health professionals should have a clear understanding of the specific needs of violinists. Playing posture, biomechanics of playing and muscle strength must be assessed to design an appropriate treatment program. Ideally, both prevention and treatment are offered within the context of playing, simultaneously improving violinists’ musculoskeletal health and performance quality, and helping them sustain a healthy and thriving life in music.

References

Ackermann, B., & Adams, R. (2003). Physical characteristics and pain patterns of skilled violinists. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 18(2), 65-71.

Ackermann B., Driscoll T., & Kenny D.T. (2012). Musculoskeletal pain and injury in professional orchestral musicians in Australia. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 27(4), 181–187.

Ackermann, B. J., Guptill, C., Miller, C., Dick, R., & McCrary, J. M. (2022). Assessing Performing Artists in Medical and Health Practice—The Dancers, Instrumentalists, Vocalists, and Actors Screening Protocol. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 21(12), 460-462.

Alinia, N., Norasteh, A. A., Majlan, A. S., & Zarei, H. (2019). The Effect of Selected Exercise Program on Musculoskeletal Pain of Neck and Shoulder in Violinist. Journal of Clinical Physiotherapy Research, 4(1), e4-e4.

Araújo, N. C. K. D., Cárdia, M. C. G., Másculo, F. S., & Lucena, N. M. G. (2009). Analysis of the frequency of postural flaws during violin performance. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(3), 108-112.

Baadjou, V. A., Roussel, N. A., Verbunt, J. A. M. C. F., Smeets, R. J. E. M., & de Bie, R. A. (2016). Systematic review: risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Occupational Medicine, 66(8), 614-622.

Blanco-Piñeiro, P., Díaz-Pereira, M. P., & Martínez, A. (2015). Common postural defects among music students. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 19(3), 565-572.

Brandfonbrener, Alice G. (2000). Epidemiology and risk factors. In R. Tubiana & P. C. Amadio (Eds.), Medical Problems of the Instrumentalist Musician (pp. 171- 194). Martin Dunitz Ltd.

Briel, S., Olivier, B., & Mudzi, W. (2020). An electromyographic and kinematic study of the scapular stabilisers. The South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 76(1).

Chan, C., & Ackermann, B. (2014). Evidence-informed physical therapy management of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 88345.

Chan, C., Driscoll, T., & Ackermann, B. J. (2014). Effect of a musicians’ exercise intervention on performance-related musculoskeletal disorders. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 29(4), 181-188.

Clark, T., Lisboa, T., & Williamon, A. (2016). Learning to be an instrumental musician. In I. Papageorgi & G. Welch (Eds.), Advanced Musical Performance: Investigations in Higher Education Learning (pp. 287-300). Routledge.

Cresswell, A. G., Grundström, H., & Thorstensson, A. (1992). Observations on intra‐abdominal pressure and patterns of abdominal intra‐muscular activity in man. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 144(4), 409-418.

Dawson, W., 2002. Upper-extremity problems caused by playing specific instruments. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 17, 135–140.

Détári, A. (2022). Musician’s Focal Dystonia: A new, holistic perspective (Doctoral dissertation, University of York).

Détári, A., & Nilssen, T. M. (2022). Exploring the impact of the somatic method ‘Timani’on performance quality, performance-related pain and injury, and self-efficacy in music students in Norway: an intervention study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 834012.

Dos Santos, F. C. L., de Souza, F., Barajas, F. H., Manco, O. U., & João, S. M. A. (2024). Odds ratio of occurrence of pain, postural changes, and disabilities of violinists. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 39, 356–363.

Farruque, S., & Watson, A. H. (2016). Developing expertise and professionalism: health and well-being in performing musicians. In Advanced musical performance: Investigations in higher education learning (pp. 319-331). Routledge.

Guptill, C., & Zaza, C. (2010). Injury prevention: What music teachers can do. Music Educators Journal, 96(4), 28-34.

Hildebrandt, H., Margulies, O., Köhler, B., Nemcova, M., Nübling, M., Verheul, W., & Hildebrandt, W. (2021). Muscle activation and subjectively perceived effort in typical violin positions. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 36(3), 207-217.

Hodges, P. W., & Richardson, C. A. (1997). Feedforward contraction of transversus abdominis is not influenced by the direction of arm movement. Experimental Brain Research, 114, 362-370.

Hodges, P. W., Cresswell, A. G., Daggfeldt, K., & Thorstensson, A. (2001). In vivo measurement of the effect of intra-abdominal pressure on the human spine. Journal of Biomechanics, 34(3), 347-353.

Jørgensen, H. (1997). Time for practicing? Higher level students’ use of time for instrumental practicing. In H. Jorgensen & A.C. Lehmann (Eds.), Does practice make perfect? Current theory and research on instrumental music practice (pp. 123–140). Norges musikkhogskole, Oslo.

Jørgensen, H. (2001). Instrumental learning: is an early start a key to success?. British Journal of Music Education, 18(3), 227-239.

Kim, S. H., & Park, K. N. (2014). The strength of the lower trapezius in violinists with unilateral neck pain. Physical Therapy Korea, 21(4), 9-14.

Kochem, F. B., & Silva, J. G. (2017). Prevalence and associated factors of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in Brazilian violin players. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 32(1), 27-32.

Kok, L. M., Haitjema, S., Groenewegen, K. A., & Rietveld, A. B. M. (2016). The influence of a sudden increase in playing time on playing-related musculoskeletal complaints in high-level amateur musicians in a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One, 11(9), e0163472.

Kok, L. M., Huisstede, B. M., Voorn, V. M., Schoones, J. W., & Nelissen, R. G. (2016). The occurrence of musculoskeletal complaints among professional musicians: a systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89, 373-396.

Laseur, D. J. G., Baas, D. C., & Kok, L. M. (2023). The Prevention of Musculoskeletal Complaints in Instrumental Musicians: A Systematic Review. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 38(3), 172-188.

Lederman, R. J. (1996). Long thoracic neuropathy in instrumental musicians: an often-unrecognized cause of shoulder pain. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 11, 116-119.

Lindman, R., Eriksson, A., & Thornell, L. E. (1990). Fiber type composition of the human male trapezius muscle: Enzyme‐histochemical characteristics. American Journal of Anatomy, 189(3), 236-244.

Margulies, O., Nübling, M., Verheul, W., Hildebrandt, W., & Hildebrandt, H. (2023). Determining factors for compensatory movements of the left arm and shoulder in violin playing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1017039.

Matei, R., & Ginsborg, J. (2022). Health education for musicians in the UK: a qualitative evaluation. Health Promotion International, 37(2), daab146.

McCrary, J. M., Ackermann, B. J., & Halaki, M. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of upper body warm-up on performance and injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(14), 935-942.

Norton, N. C. (2016). Health promotion in instrumental and vocal music lessons. The teacher’s perspective (Doctoral dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University and Royal Northern College of Music).

Nyman, T., Wiktorin, C., Mulder, M., & Johansson, Y. L. (2007). Work postures and neck–shoulder pain among orchestra musicians. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 50(5), 370-376.

Park, K. N., Kwon, O. Y., Ha, S. M., Kim, S. J., Choi, H. J., & Weon, J. H. (2012). Comparison of electromyographic activity and range of neck motion in violin students with and without neck pain during playing. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 27(4), 188-192.

Polnauer, F. F. (1952). Bio-mechanics, a new approach to music education. Journal of the Franklin Institute, 254(4), 297-316.

Prescher, A. (2000). Anatomical basics, variations, and degenerative changes of the shoulder joint and shoulder girdle. European Journal of Radiology, 35(2), 88-102.

Rousseau, C., Taha, L., Barton, G., Garden, P., & Baltzopoulos, V. (2023). Assessing posture while playing in musicians–A systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 106, 103883.

Savino, E., Iannelli, S., Forcella, L., Narciso, L., Faraso, G., Bonifaci, G., & Sannolo, N. (2013). Musculoskeletal disorders and occupational stress of violinists. Journal of Biological Regulators & Homeostatic Agents, 27(3), 853-859.

Steinmetz, A., Seidel, W., & Muche, B. (2010). Impairment of postural stabilization systems in musicians with playing-related musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 33(8), 603–11.

Steinmetz, A., Seidel, W., & Niemier, K. (2008). Shoulder pain and holding position of the violin. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23(2), 79-81.

Steinmetz, A., Scheffer, I., Esmer, E., Delank, K. S., & Peroz, I. (2014). Frequency, severity and predictors of playing-related musculoskeletal pain in professional orchestral musicians in Germany. Clinical Rheumatology, 34, 965-973.

Voight, M.L., & Thomson, B.C. (2000). The role of the scapula in the rehabilitation of shoulder injuries. Journal of Athletic Training, 35, 364–372.

Waters, M. (2020). The perceived influence of the one-on-one instrumental learning environment on tertiary string students’ perceptions of their own playing-related discomfort/pain. British Journal of Music Education, 37(3), 221-233.

Wilke, C., Priebus, J., Biallas, B., & Froböse, I. (2011). Motor activity as a way of preventing musculoskeletal problems in string musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26(1), 24-29.

Zaza, C. (1994). Research-based prevention for musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 9(1), 3-6.

Zaza, C. (1998). Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. Cmaj, 158(8), 1019-1025.

Zaza, C., Charles, C., & Muszynski, A. (1998). The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders to classical musicians. Social science & medicine, 47(12), 2013-2023.

Zaza, C., & Farewell, V. T. (1997). Musicians' playing‐related musculoskeletal disorders: An examination of risk factors. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 32(3), 292-300.

Zinn-Kirchner, Z. M., Alotaibi, M., Mürbe, D., & Caffier, P. P. (2023). For fiddlers on the roof and in the pit: Healthcare and epidemiology of playing-related problems in violinists. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 16, 2485-2497.

Comments